|

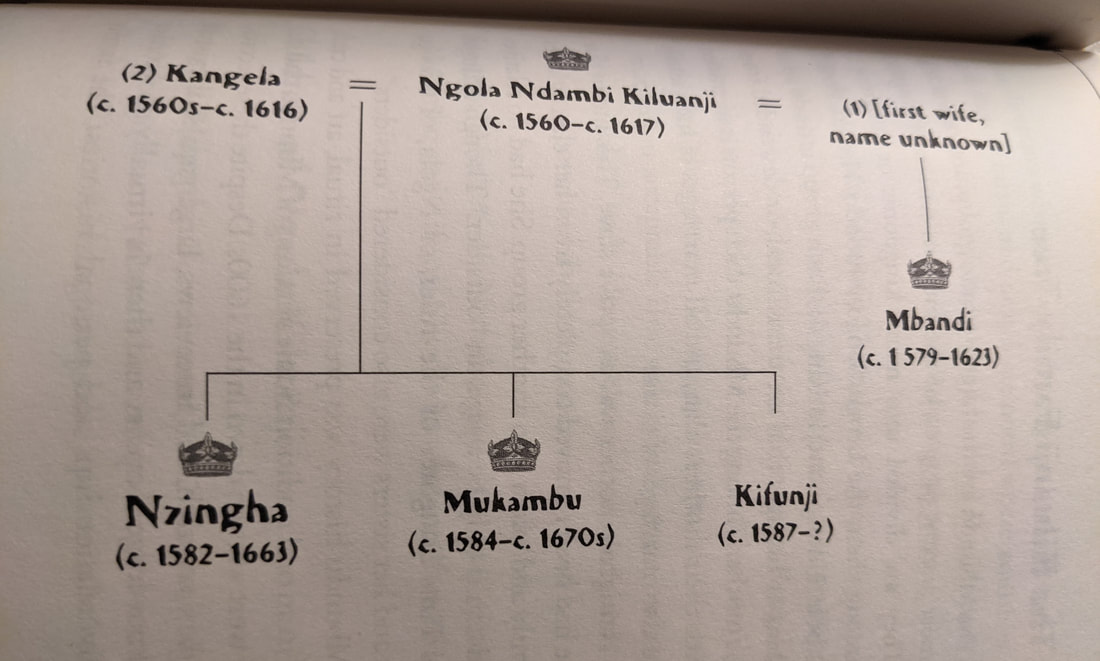

Njinga of Ndongo (Africa’s present day Angola region) was a strong female African warrior of historical importance because of her sustained resistance waged against the colonial might and trickery of the Portugese. She was born to Ndambi Kiluanji, the king of the Mbundu people and Kangela, his first wife in 1583 (exact date unknown). Because of the customs of her people restricting leadership to a male heir, she was not allowed to become the next ruler after her father died. Instead, her half brother, Mbandi took the throne. After her brother died, she took the throne and used her skills to fight the colonial expansion of the Portugese for almost 40 years. She died on December 17th, 1663.

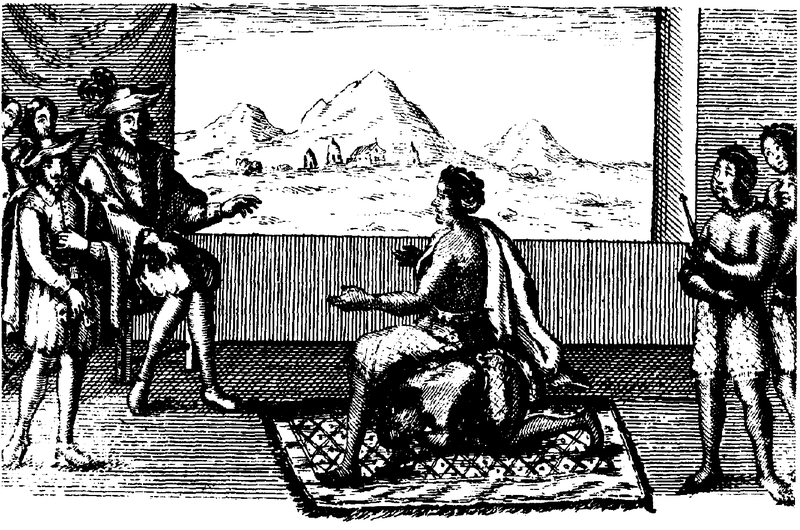

Her life was fascinating and filled with many challenges she overcame with keen strategy and physical prowess. One of her most discussed accomplishments involved a peace treaty she negotiated with the Portugese. Shown in the illustration (see Picture 1), I would like to analyze this scene as discussed in the book, “Between the World and Me” by Ta-Nehisi Coates released in 2015.  Picture 1: Drawing of Njinga (not yet Queen) negotiates on behalf of her brother with the Portugese Governor, Correia de Sousa. Illustration is extracted from the book "Zingha, Reine d'Angola. La Relation d'Antonio Cavazzi de Montecucculo. Picture taken is in the public domain on https://commons-wikimedia-org.translate.goog/wiki/File:Queen_Nzinga_1657.png?_x_tr_sl=pt&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en-US&_x_tr_pto=ajax,se,elem,sc  Professor Linda Heywood of Howard University was catapulted into the spotlight when Ta-Nehisi Coates mentioned her in his book, “Between the World and Me.” In the book, Coates said that his perspective changed on African history from a romanced “Tolstoy” version to one that was more realistic and included different perspectives. The prepackaged and pre-approved version that some classrooms present can be stuffy and could omit opposing views. It’s a valid point. He says when starting his studies at Howard, “I had come looking for a parade, for a military review of champions marching in ranks. Instead I was left with a brawl of ancestors, a herd of dissenters, sometimes marching together but just as often marching away from each other.” I agree that we should all come to our own conclusions and interpret history from a broad perspective; always question the agenda of the author of the history book, and even ask what the race of the author is. In the words of Marcus Garvey, “read with observation” and understand that authors write from their own point of view, and finally, ask if it all makes sense. Though Coates came to this conclusion after considering a different perspective to a famous historical memory in Njinga’s life, I respectfully take issue with his interpretation. I’m glad he pivoted to a more realistic view of history, but the confusion he created about Njinga’s original intentions was in error. On top of that, he should have reviewed the facts in his story.

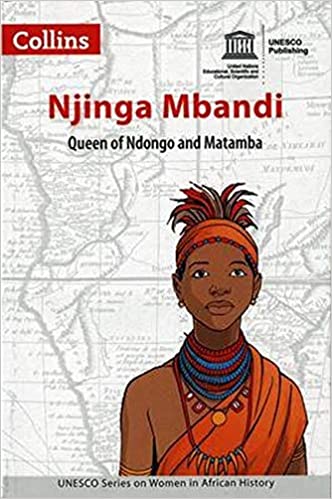

Let’s back up a bit and examine the description of the scene in the picture closer. We’re in 1622. Njinga goes to meet with the Portugese Mayor of Luanda, on behalf of her half brother (King Mbandi). Please note: She was not Queen at this time. Upon her arrival to his audience chamber, she noticed the Mayor had prepared a chair of state for himself and a pillow on a rug for her to sit. This meant, “that the Portuguese saw her as a subordinate” according to an article I had translated called, “Njinga Mbandi: the symbol of African resistance to Colonialism.” She refused to be disrespected even in the slightest. Outraged but able to quickly pivot into a more acceptable exchange between two heads of state, Njinga nodded to one of her “attendants” to become a chair by getting down on all fours. The rug and pillow were routinely used to negotiate with what were considered as “conquered” Africans, according to Coates’ Professor. [1] Well, I think Coates’ response to this scene was an unnecessary and misplaced agitation. So be it that this was the straw to break his Tolstoy’d Black History camel’s back, (pun intended) but my goodness, why did it have to come at the expense of misrepresenting Njinga’s intentions. In every reference I’ve read, and in understanding the wider context, Njinga was not merely showing her power to tell one of her adviser’s what to do. She was instead responding to the insult initiated by the Govenor who did not dignify her with even a chair to sit across from him in negotiations. He left a rug and a pillow which Njinga quickly understood meant that she was not seen as his equal. That is the issue. I do not understand why Coates skirts past this egregious indignity to take her actions out of context. In a lecture presented to the Library of Congress (https://youtu.be/GxpswAL_9_U) by Coates’ Professor available on youtube 3 years after his book comes out, revisits her description of the famous historical scene between Nzingha and the Portugese Mayor at 21:07. She said, “Njinga had to show her status was equal to the Portugese.”. In another video, his Professor further separates her student’s off-key response from her own by saying, at 15:12 the carpet was laid out across from the Portugese for, “Africans who had been conquered” Njinga refused to sit. …”we can say, O how cruel, but Njinga’s strategy was for the Portugese to know that they weren’t dealing with an African who’d been conquered.” Coates was saying in essence, O how cruel. He focused on the body of the advisor and missed the point, entirely. Sorry, not sorry. When Njinga called her advisert to come over….Njinga’s strategy was for the Portugese to know that they were not dealing with a defeated African” in the words of Coates’ own Professor. This heartened me. When I initially read Coates’ rendition of this event, I was fuming since Njinga is one of my sheroes (my name was chosen in honor of her), and he appeared to completely misrepresent the raison d-etre of her actions to her “adviser.” When Coates says Njinga was “heir to everything she’s ever seen.” I say, not this queen. Njinga earned her position and was loved by her people. She was not like the royalty he had been exposed to. Njinga was not even the heir to the throne, and that was the problem. She had to fight, go into hiding, and other creative means to take her position because her brother was the rightful heir. Thankfully, the Portugese would remove their troops after that famous meeting, for the time being. I don’t think Coates’ meant to create chaos as much as I think he just realized that the more you know, the more you realize how much you don’t know. And that’s ok. We’re all growing into our own and it is useful to witness his coming of age at Howard. And there’s plenty more learning to do. I am thankful that his book drew a new readership. Full disclosure, I’ve sold many of his books. But as he points out so well, we are not all on the same accord and can come to our own conclusions. I don’t think he ever presented his book as a history book, and it is just his opinion and interpretation. And that is good. Was Nzinga a Real Person?But the controversy surrounding Njinga doesn’t not stop there, it gets worse. In my earlier blog post, “Was Hannibal Black” about Hannibal Barca for example, his image is often depicted as non-African, though he was of African origin. In the case of Njinga, there is much discussion about whether she was even a “real person.” There is one post called, “ Nzinga Mbandi: From Story to Myth.” The article is written by 3 Portugese students that allege that descriptions of her reign conflict with each other and are based on an historian who “was seduced” by the black queen. Part of their abstract states that the "nationalist exaltation" is just a vain attempt to create facts from fantasy. They say in part that this is “an evident strategy which, by the rescue of figures and cultural practices, is defined as a means to affirm negritude.” Sigh, copyright matters. When I looked into the copyright of the works that were analyzed, they were from 1975, 2007, 2014 respectively. They mentioned further that the three authors’ work was based on the earliest copyrighted work of Castilhon of 1769. But this isn’t a credible source either since his work was published over 100 years after Njinga’s death. The last author mentioned is Cavazzi who did live during her reign. Based on a newer translation, John Thornton did, all commentary should be revisited after reading that “Africanists” would be quite interested in the results.[2] I was happy to hear Linda Heywood mention that she was able to see the manuscripts written by Cavazzi directly and that Njinga was “definitely a real person.” She noted that some material was not in the published work and vice versa. In one of her videos she also states she is writing a second book about Njinga. ConclusionThe full account of Njinga's exciting life story has yet to be written. Certainly it is inspiring given the time period of her reign. Starting from her preparedness for leadership but restriction from the throne to negotiations with the Portugese. Primary research is more important than ever. Thankfully, technology, curious minds, and yes mainstream exposure brings us closer to uncovering it. This post is fashioned to raise your awareness on the topic so you can jump in and add to the conversation. Want more?As always, I appreciate that you have read through this blog post. I hope that you’ve become curious to find out more and do your own research. We ask that you consider purchasing your books from our Black owned business, Afriware Books, Co. If there is a title you’d like to purchase that is not mentioned here, or could not be found on the website, feel free to email us at: [email protected] Blog Notes [1] Youtube video presentations by Linda Heywood at: https://youtu.be/GxpswAL_9_U and https://youtu.be/GxpswAL_9_U [2] John Thornton accepted a NEH grant to do an edition and translation into English of Volume A of Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi’s detailed at this important website: http://www.bu.edu/afam/people/faculty/john-thornton/cavazzi-missione-evangelica-2/ Bibliography includes all books mentioned in this post. When you are using google to find out more about this African Queen, it will be important to use alternate spellings: Nzingha Njinga - Kimbundu spelling. Njinga was a member of the Kimbu group. Njingha - Nzingah Jinga or Ginga Also, depending on the role she was about to perform on behalf of her people, she would change her name. In some circles, she would only be recognized if she was a “king” so she dressed like a king and demanded to be called king. These iterations of her name are taken from “Njinga Mbandi - Queen of Ndonga and Matamba” UNESCO Series on Women in African History” comic strip illustrations by Pat Masioni, Script by Sylvia Serbin, Edouard Jabeaud, 2015: Njinga Mbande, Njinga Mbandi, Nzinga, Jinga, Singa, Zhingha, Ginga, Njingha, Ana Njinga, Ngola Njinga, Njinga of Matamba, Zinga, Zingua, Mbande Ana Njinga, Ann Njinga and Dona Ana de Sousa. Additional References

My absolute favorite film: (English subtitles) BBC News Africa did a documentary on Njinga showing the towering statue here: https://youtu.be/W0v_SwObQns, view at 10:32. Show’s “17th century illustration” shows Nzingha seated on “male” servant… BBC Brasil posted an article that I translated into English here: https://www.conexaolusofona.org/njinga-mbandi-o-simbolo-da-resistencia-africana-face-ao-colonialismo/ . Comments are closed.

|

AUDIOBOOKSMERCHGIFTSjoin email listACADEMIC BOOKSblog Author/

|

- Store

- Blog

- AUDIO BOOKS

- EBOOKS

- SEARCH

- Welcome

- GoFundMe

- TUCC

- Events

- READING GUIDE

- AUTHOR INFORMATION

- ARTIST BIO/PRICE

- NNEDI OKORAFOR BOOKS

- PODCAST

- LARUE'S HAND IN CLAY

- About Us

- FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

- BOOK FAIR /SCHOOLS / CLUBS

- Photo Gallery

- EJP BOOK DRIVE

- Videos

- Newsletter/Articles

- Archives

- External Links

- Afriware Statement on COVID-19

- GREATER LAKES

- Afriware Merchandise

- AFFILIATE INFO

- SEBRON GRANT ART DESIGNS

- Mother's Day Bundles

- CARTOON

- ROBOTS

- STEM

AFRIWARE BOOKS CO. A COMMUNITY BOOKSTORE SERVING:

|

|

Melrose Park, IL

|

|

,AFRIWARE BOOKS, CO,

1033 SOUTH BOULEVARD, OAK PARK, IL 60302 708-223-8081 ONLINE SUPPORT: Thurs-Fri. 4-6pm Sat. 12-2pm, IN PERSON EVENTS: afriwarebooks.com/events |

Want to try a great website builder, try Weebly at: https://www.weebly.com/r/9SAD4V

RSS Feed

RSS Feed